we built a bridge - CIV102 Bridge Project

CIV102 Bridge Project

The project handout this year can be found here.

If you have any questions, feel free to contact me at [email protected] with a subject line starting with “CIV102BP”. I was in charge of programming and the key designs, including the triangular and X diaphragms, so I can answer most questions.

Following the “deductive arrangement” we learned in Praxis, I put the test results before the design and build sections.

Test Results

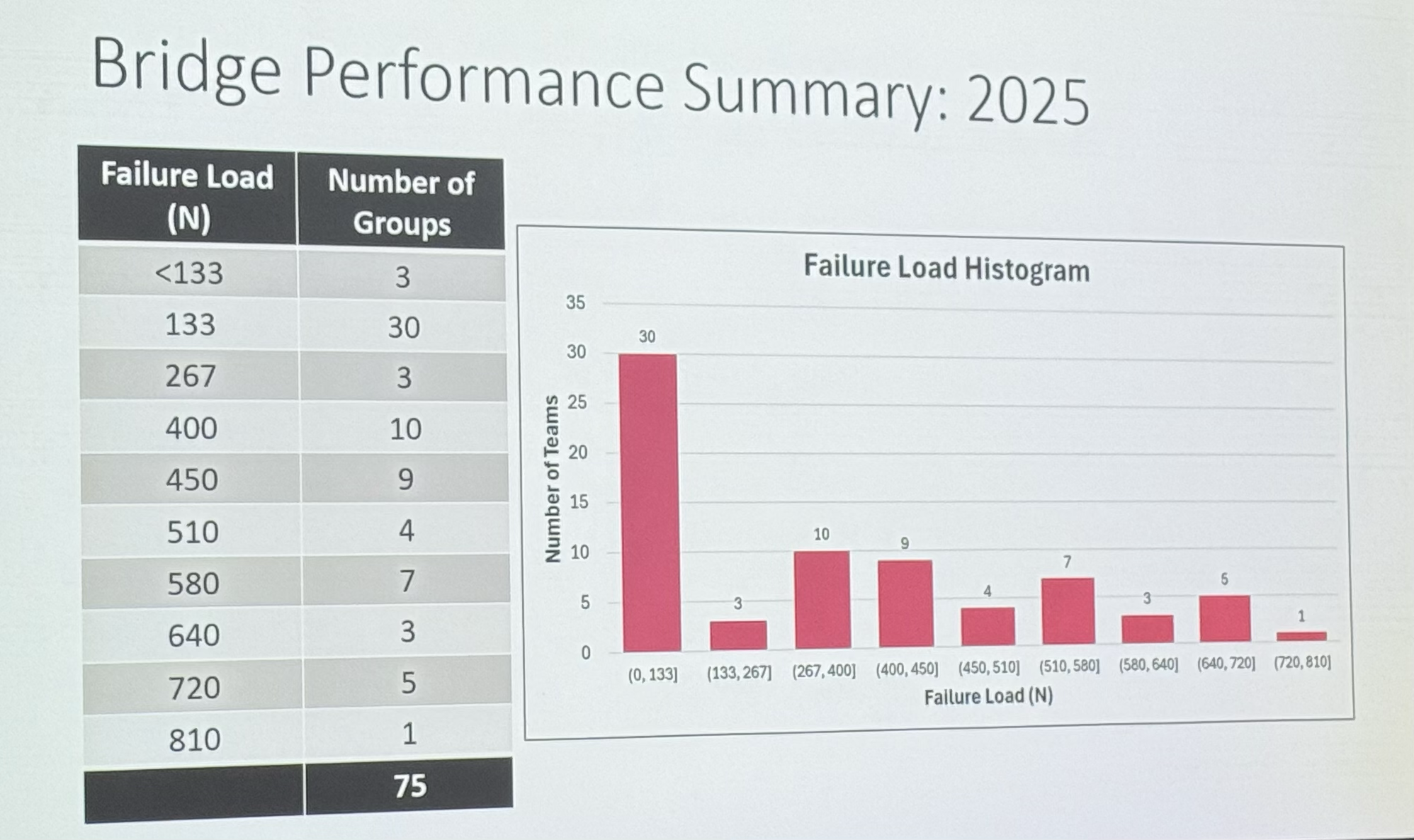

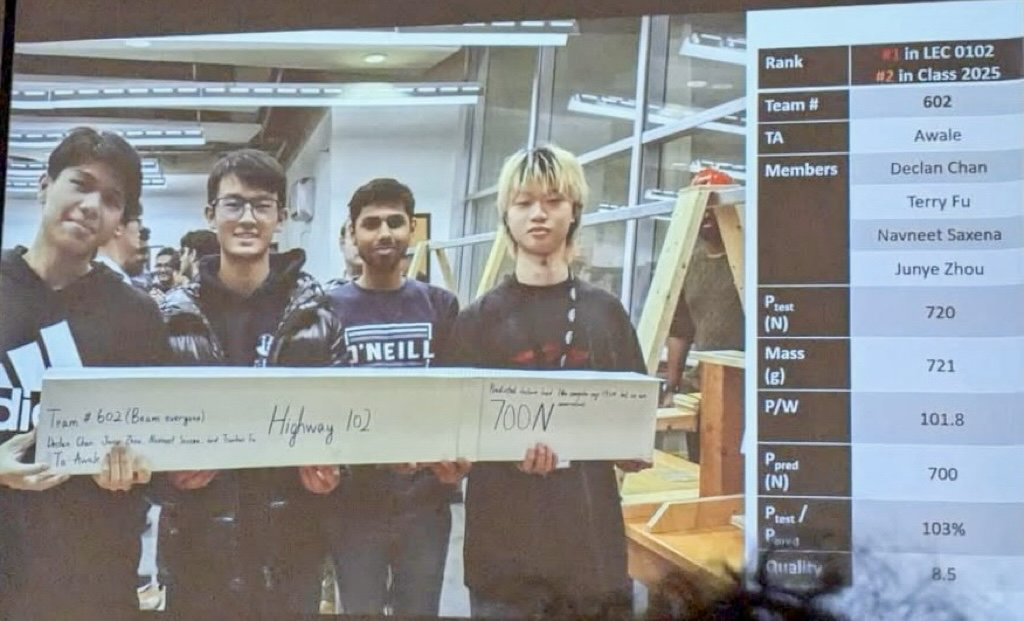

Our bridge was tested on Tuesday, 2025-11-25. The maximum load of our bridge was 720 N with a mass of 721 g, which made us top 1 in our cohort and 2nd in the class of 2025. We had a quality mark of 8.5 / 10. Note that the maximum load was actually somewhere between 720 N and 810 N, but since there was no intermediate testing load, it could only be either 720 N or 810 N.

They calculated the $\frac{P}{W}$ ratio wrong, but the ranking was good. The 3rd and 4th in the class were both 759 g.

The following video shows the bridge failing when an 810 N train tried to pass. You can see that the uneven top flange triggered the buckling of the side walls when the wheel was stuck in the bump.

The bridge broke at the center instead of the splice, meaning that we did a pretty good job designing and manufacturing the bridge. In the future, if you want to improve the maximum load, you can try, near the center, putting more diaphragms inside and small triangular limiters outside to prevent buckling of the walls.

Designs

Design 1: Uniform Cross-section

We started everything by writing the code. I strongly recommend you keep a unit test that calculates everything you have for Deliverable 1, because as you modify your project, it is very likely some parts will go off. Keeping the unit test can verify that new changes do not have a negative impact on the other functionalities. In our repository, you can find the unit test here. Another thing I knew before putting my hands on the framework was that it needs to be modular. Although if you use our solution, you probably do not care about the philosophy behind programming, but if you decide to write your own code, I recommend you keep a similar structure as ours. The biggest difficulty I had was implementing automatic composition of complex cross-sections. Since in the handout they want us to be analytical, I had never thought about writing the framework in differentiable tensors, though if you use PyTorch, the optimization process will be much faster.

The link to our repository can be found on the top of this page.

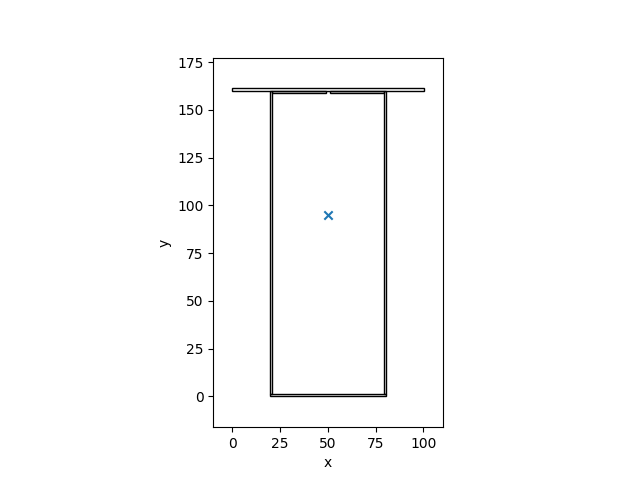

Once you have the framework, you can start optimizing the dimensions of the cross-section. In this file we acquired the optimal cross-section to be {"top": 100.2, "bottom": 60.7, "height": 160, "thickness": 1.27, "outreach": 28}. You can find a reference of what these dimensions are in “cross_section.py” . This was basically our Design 1. By manually changing the distance between diaphragms, we knew that once the spacing goes below 140 mm, it no longer changes the maximum load. So we decided to have 9 intervals and 10 diaphragms.

We know that having a small anti-smile curve is going to help resist the positive bending moments. So we decided to model the impact of increasing the height of the center 1/3 of the beam by another layer of matboard (1.27 mm). In “design1.py” we calculated that a uniform beam resists 1193 N and with the slight curve it goes up to 1204 N. Therefore, we built our prototype with the curve.

Design 2: Varying Cross-section

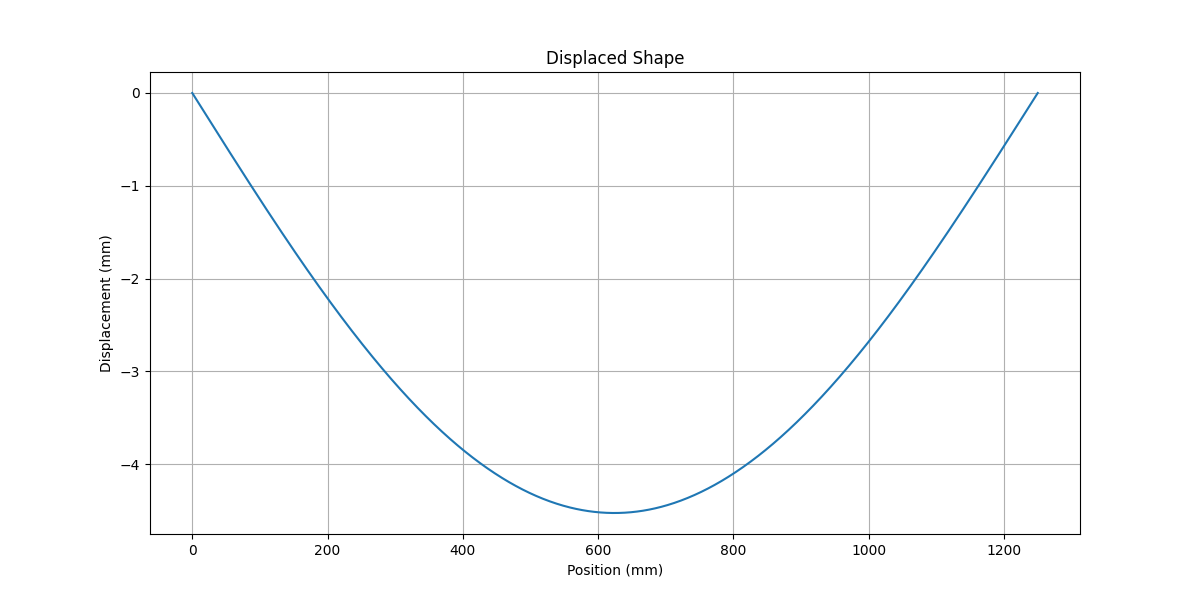

By looking at the formulas $\tau=\frac{VQ}{Ib}$ and $\sigma=\frac{My}{I}$, we knew that at the ends, where the shear force is the largest, we wanted smaller Q values to bring down the stress caused by the shear force, whereas close to the center, where the bending moment dominates, we wanted larger I values so that the moment-related stresses can be dissipated. Thus, we know that the height of the cross-section should be increasing on each half of the bridge. We calculated both trapezoid and parabolic shapes in “design2.py”. The trapezoid was much easier to build, so we went with that for the second prototype.

Also, if we compare the displaced shapes of Design 1 and Design 2, we can see that the trapezoid does reduce the deformation.

Prototypes

We knew we were gonna f**k up the first try, so we bought 3 matboards with the identical dimensions and color from Michaels Custom Framing Department. Another reason for prototyping was that we had two designs (Design 1 and Design 2) and we wanted to compare them. We used hot glue gun instead of the glue cement so that it did not take three days before we could test them.

Design 1

If you are building your bridge in the same orientation, meaning that the open end of the U shape is in contact with the top flange, we suggest you glue it in the same sequence as we did.

Our bridge consisted of two segments, connected by a splice at the 2/3 position. The top flange was split at the 1/3 position. We put our rectangles in optiCutter to plan our cutting. Our plan PDF is available here.

In our first prototype, our cutting skill was terrible. We later learned that we should have scored the lines with a ruler before cutting. We improved in the final manufacturing. However, the bad cutting quality resulted in the fact that none of the diaphragms in the first prototype had the same height or touched the top flange. We had to add small pieces to fill the gaps.

We had even spacing for the diaphragms, however, since the shear forces at the two ends are significantly higher, we need better support. What we did initially was folding one diaphragm into an isosceles triangle without the hypotenuse on each end. The joint diaphragm at the splice was also folded in the same way so it connects the two segments.

We glued all the diaphragms in the small segment to the bottom and one side, and then glued the other side before we sealed the top. The second step was to glue the joint diaphragm onto the large segment and then follow the same procedure as the first step to close the large segment. The third step was to wrap the splice with a thin matboard. After that, the final step was to glue the top flange on the bottom U shape.

We tested the beam by me sitting on it. We can see that the two ends failed due to the buckling of the triangular diaphragms as well as the walls. Therefore, we knew that we needed stronger support at the two ends. We built a small sectional testing frame to test different diaphragms. A larger 45-degree right triangle with the hypotenuse touching both sides was determined to be the best, although it still failed due to nonaxial torque when our heaviest member stepped on it. The picture below has an open edge, that was because we glued it back after it was broken, it should be a closed edge.

We replaced the broken small triangular diaphragms in the first prototype with two of these new designs.

When I first sat on the bridge at the splice, it did not fail at all, so another team member came and sat in the middle, and the bridge broke at the splice. The joint diaphragm was not damaged or buckled, it simply shifted. The glue under the wrap also failed. This result was intuitive and expected because at the splice the bending moment was way more significant than the shear force. That was why we later introduced a thick inner connection for the final bridge.

Design 2

The trapezoid bridge was so time-consuming and hard to build as it took so much gluing, thus, it ended up being just a sketch as we ran out of time.

Final Product

In the final bridge, we made four major updates. Find the interior schematic diagram attached.

- We added a connection stripe at the inner bottom of the splice. When the bending moments try to detach the bottom of the two segments, the stripe exerts a plane tension to resist that deformation.

- We increased the width of the outer wrap at the splice for the same purpose as the stripe.

- We replaced the old joint diaphragm with a new cross-like diaphragm. We tested the X diaphragm with a clamp. It was challenging to destroy it. It also provided a larger contact area.

- For the two large triangular diaphragms, we added an overlapping edge for better gluing.

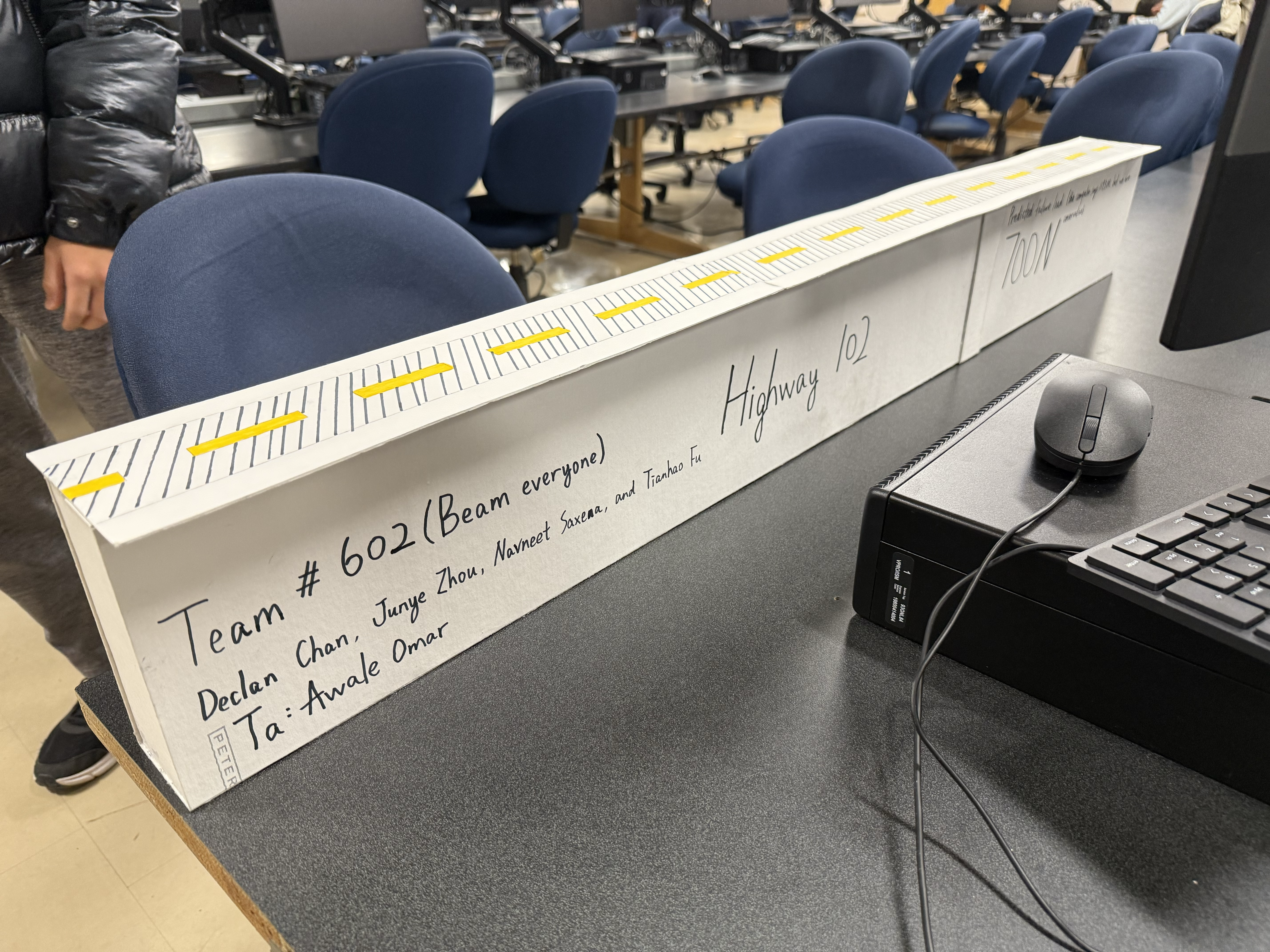

Team 602

Authors

Sorting follows alphabetic order of the first name initials and does not reflect contributions. The hyperlinks refer to portfolios.

D. Chan, J. Zhou, N. Saxena, and T. Fu

Team Name: Beam Everyone

“Beat everyone” but “beam”.

Bridge Name: Highway 102

We picked this name not only because the course name is CIV102, but also because Ontario highways are named such that Highway 404 means there are four lanes. Our bridge only had one lane, so it made perfect sense.

Citation

The following citation is for our design report, not the blog post.

@techreport{team602civ102,

title = {CIV102 Bridge Project Design Report},

author = {Chan, D. and Zhou, J. and Saxena, N. and Fu, T.},

institution = {Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering, University of Toronto},

year = {2025},

month = {November},

type = {Course Project Report},

course = {CIV102: Structures and Materials},

note = {Team 602}

}

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Fu, Tianhao (Nov 2025). we built a bridge - CIV102 Bridge Project. Tianhao Fu. https://atatc.me.

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{fu2025we-built-a-bridge-civ102-bridge-project,

title = {we built a bridge - CIV102 Bridge Project},

author = {Fu, Tianhao},journal = {Tianhao Fu},

year = {2025},

month = {Nov},

url = {https://atatc.me/blog/2025/bridge/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: